15 Years of Gender Quotas in Burundi: What’s the Impact?

Burundi organized its forth post-conflict general election in 2020, a year that also marks the 15th anniversary of the implementation of gender quotas in politics. Have gender quotas changed the face of Burundi’s government—or the content of decisions taken by the government?

The Introduction of Gender Quotas

The 2005 Constitution of the Republic of Burundi (articles 129, 164, 182(2)) introduced a requirement that women hold a minimum of 30% of seats in Parliament—both in the National Assembly and in the Senate—and in the Executive branch. This measure aimed to address Burundian women’s historical underrepresentation in public life since the country’s independence in 1962. In fact, archives show that while women were elected in parliament for the first time in 1982, and appointed to the Executive branch for the first time in 1984, their representation in those bodies had consistently fluctuated around 10 percent until 2005. Even after the 1993 elections when Sylvie Kinigi was appointed the first-ever woman Prime Minister in Burundi, women accounted for only 2 out of 23 cabinet members and 8 out of 81 of members of the single-chamber parliament or National Assembly.

The Impact of Gender Quotas on Women’s Political Influence.

The 2005 general elections, the first test of the gender quota, resulted in historic gains for women. Women’s representation jumped from 12% to 36.8%, from 19% to 31%, and from 18.8% to 34.6% in the Executive branch, the National Assembly (upper chamber), and the Senate, respectively. Women inherited the positions of Speaker of the National Assembly and 2nd Vice-President of the Republic. The same trend continued steadily until today. During the 2015-2020 period (the last legislature governed by the 2005 constitution) women represented 36.36% of members in parliament and 31.8% of officials in the executive branch.

In other institutions and decision-making bodies where the 30% minimum quota for women was not specifically required—including in public administration at large, diplomatic posts, the judiciary, and defense and security forces—the 2005 Constitution instead mandated “gender equilibriums” (art. 135, 208, 255). This mandate, too, was fairly followed. Today, women make up at least 30% of members at important national institutions, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR Burundi), the National Independent Commission on Human Rights (CNIDH), and the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI Burundi). In 2011, the Burundian legislature even went as far as to require a minimum of 30% women in the compositions of national and provincial executive committees of political parties (art. 33 of the law of political parties).

Why Gender Quotas Came at the Right Time

The introduction of gender quotas in 2005 in Burundi came when women were still suffering from the existence of some discriminatory laws, harmful gender norms, and patriarchal practices.

First, there was a legal vacuum concerning matters of inheritance, matrimonial regimes, and gifts that resulted in women’s inability to enjoy the same land right as men.

Second, the 1993 Personal and Family Code contained discriminatory provisions that codified cultural traditions that advantaged men over women. These include article 38, which set the age of marriage at 21 for men and 18 for women, and most importantly, article 122, according to which “the husband is the head of the conjugal community” (emphasis added).

Third, under the Nationality Law of 2000, women married to foreigners had to go through a long, costly, and complicated process to pass their Burundian nationality to their husbands and children. However, Burundian men could pass their nationality to foreign-born spouses through a simple declaration (Law n. 1/013 of July 18, 2000, reforming the Nationality Code of Burundi, articles 4 and 10).

Fourth, only women could be punished for the crime of adultery under the 1981 Penal Code (article 362).

Fifth, women on maternity leave could only get half of their salary by application of the Labour Code of 1993 (art. 123 para 4).

One could argue that these double standards existed because women had been excluded from decision-making for a long time. With the unprecedented increase of women in decision-making bodies through gender quotas since 2005, many Burundians hoped that those women would bolster positive change and push for more equality between men and women. This notion—that putting women in power will advance gender equality—is also supported by research. According to the CEDAW Committee in its General Recommendation 23 on Political and Public Life, when women’s representation in decision-making reaches a critical mass (30-35%), “there is a real impact on political style and the content of decisions, and political life is revitalized.” Other studies have reached a similar conclusion.

Given that women in Burundi achieved “critical mass” in the legislative and executive branches of government and controlled the ministries in charge of justice, human rights, and gender inclusion, many Burundians expected them to make significant progress for their countrywomen during the 2005-2020 period.

What Has Changed after 15 Years?

Today, the results are mixed. On the one hand, the Burundian government has reinforced the legal protections from sexual violence and exploitation for women and girls. This includes the adoption of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography in November 2007. Additionally, we saw the reform in 2009 of the 1981 Criminal Code that punished women only for adultery, the adoption of a new law on criminal procedure in 2013 (amended in 2018) that gives civil society organizations the possibility of supporting victims of sexual violence in their quest for justice (art. 64 para 4 and 5), and the adoption of a very strong law against sexual and gender-based violence in 2016.

On the other hand, there is a regrettable persistence of discriminatory laws and harmful traditional practices that continue to perpetuate gender inequality. First, inheritance is still governed by discriminatory patriarchal traditions that prevent women from enjoying the same land rights as men. By contrast, Rwanda—often referred to as Burundi’s conjoined twin—adopted a succession law that gave women and men the same land rights in 1999. Second, the 1993 Personal and Family Code that suggests that husbands are the head of the conjugal community, the 2000 Nationality Code that uses a double standard in men’s and women’s ability to pass their nationality to their foreign-born spouses, and the 1993 Labor Code that suggests women on maternity leave only receive half of their salary are still in effect today. Besides, a presidential decree of 2017 came to reinforce inequality by preventing women from touching Burundian traditional drums, which are considered sacred (art. 3).

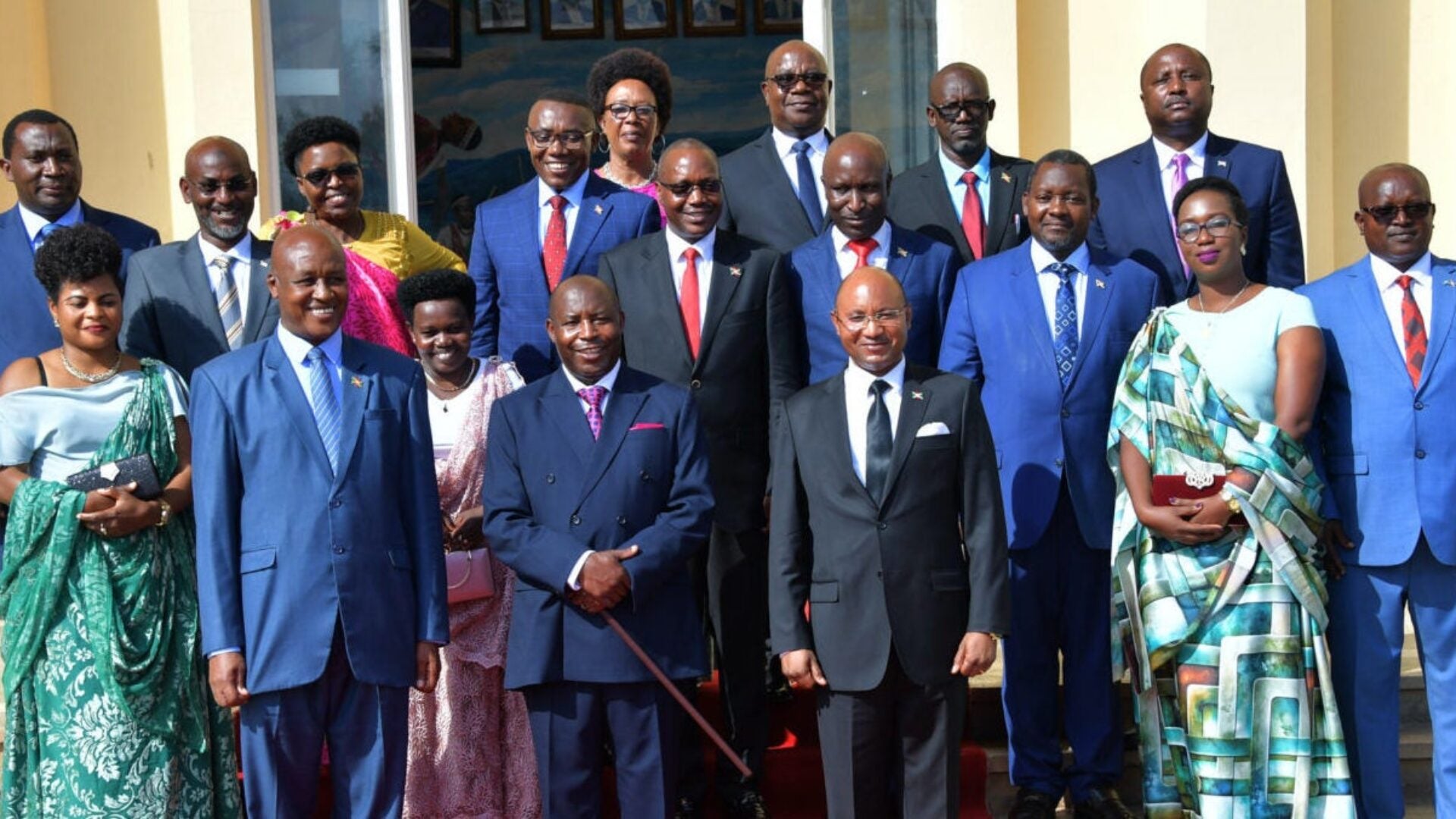

This mixed progress on gender equality during the last 15 years suggests that achieving a critical mass of women in government is a good way to begin instituting gender equality reforms, but more work remains to be done. The upcoming 2020-2027 legislature governed by the new 2018 Constitution will include even more women than the previous government, and its actions may indicate whether further increasing the number of women in decision-making positions can increase gender equality in Burundi as well. The new Constitution maintains the minimum 30% gender quota for women’s representation in the legislature and the executive branch and even extends it to the judiciary (article 213). As a result, women will have a critical mass in the three branches of state power during the 2020-2027 period. Will this accelerate the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 on gender equality? Time will tell.

Fikiri Nzoyisenga is a human rights researcher, community organizer, and gender equality activist in Burundi. He is the Founder and Executive Director of Youth Coalition Against Gender-based Violence – SEMERERA.

Want to hear more from Fikiri? We asked him about gender roles and social change in Burundi:

Explore More

End of Year Reflections

This year has been particularly challenging for peace around the world, with…

“No Amnesty, No Silence:” Ukrainian Women Urge Accountability for War-Time Sexual Violence

Last week, the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) brought…