Measuring Women, Peace and Security

By Dr. Jeni Klugman (Managing Director, GIWPS) and Dr. Marianne Dahl (Senior Researcher, PRIO)

Last week, GIWPS together with the International Peace Institute and the Government of Norway cohosted a discussion on linking the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Index to WPS in practice. The WPS Index, launched in October 2017 by GIWPS and PRIO at the United Nations, draws on recognized international data sources to rank 153 countries on peace and security—and women’s inclusion and justice—in homes, communities, and societies.

The New York discussion, held alongside the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women, touched on how the index and data more broadly can be used in advocacy efforts, challenges in collecting data in fragile or conflict contexts, and broader priorities for WPS action.

NYU Professor of Global Affairs Anne Marie Goetz reflected on the role of the WPS Index prior to the event. We appreciate her warm welcome of the WPS Index and have responded below to her important questions about how additional or different data could help to reflect the WPS agenda in the WPS Index.

In her post on the Global Observatory blog, Goetz praises the WPS Index for its simplicity, elegance, and consistency. “It enables detailed comparisons of countries, as well as the compilation of country rankings—so dreaded by governments, so useful to activists.”

She also welcomes the ways in which the new Index “makes up for the omission of gender inequality measures in conflict monitoring frameworks, state fragility analyses, political instability estimates.” She says that “it, refreshingly, combines the measures of gender inequality familiar from many gender equality indices—women in parliament and the labor force—with some that are perception-based.”

At the same time, Goetz raises several challenges related to tracking the WPS agenda.

She points to the 26 WPS indicators that have been populated in annual UN secretary-general reports since 2009 as possible indicators for a WPS index. Yet, as she recognizes: “each one is almost too anomalous to make comparative analysis meaningful.” Further, “WPS means very different things in a conflict-affected state than in others.”

GIWPS and PRIO conducted an extensive review of data sources when we embarked on the WPS Index project, and will continue to look, and advocate, for improved data to inform future iterations of the index. As Goetz and other experts recognize, we are significantly limited by data availability, reliability, comparability, and robustness.

Goetz makes the good point that measures of women’s participation in national security and foreign policy establishments, as well as their freedom to associate autonomously and influence public decision-making, would be illuminating alongside the currently available measure of participation (in parliaments) that we include in the index. While these measures cannot yet form part of the WPS Index given the limited global coverage, we do propose to deepen work and research around these issues, such as investigating relations between countries’ Index scores and measures of whether women are free to associate autonomously and influence public decision-making.

On the security front, rather than use measures like military spending that feature in other security and peace indices, we focus on aspects especially relevant to women. That is, in the household—in terms of intimate partner violence; in the community—whether women feel safe walking in their community at night; and at the country-level—through battle deaths in organized violence. As Goetz notes, this was “the first time in a gender equality-related index, levels of organized violence are included as a measure of women’s security.”

Organized violence presents a great threat to women and men, boys and girls, in many parts of the world. It would not be possible to capture how it is to be a woman in Syria today without accounting for the brutal civil war– and indeed Syria ranks (tied) last in the index.

The organized violence indicator in the index—measuring battle-deaths caused by three types of conflict (state-based, non-state and one-sided) collected by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)—is currently the “gold standard” for conflict data in quantitative research. The article that introduced these data (Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg & Strand, 2002) has been cited more than 3000 times in the academic literature, and the annual updates have been cited over 2900 times.[1] The same data underpins a range of influential global reports such as the UN’s Human Security Report and the World Bank’s “World Development Report” (2011), and in such seminal books of Steven Pinker (2011)[2] and Joshua S. Goldstein (2011)[3].

While it would be ideal to have battle-deaths data disaggregated by gender, such data does not exist, and has proven very difficult to code. However, even if only men were killed in battle, organized violence has major repercussions for women and girls off the battlefield. It is often associated with, among other things, higher maternal mortality, worsening rates of infant mortality, undernourishment, poverty, primary school enrollment, and access to potable water (Gates, Hegre, Nygård & Strand, 2012)[4], as well as higher rates of intimate partner violence in the home.

In sum, we agree that the new WPS Index is not perfect, not least because of data constraints. We very much welcome Goetz’s recognition that the new WPS Index is “a great improvement on existing indices of gender equality or of women’s empowerment.” Looking ahead, we do hope that the explicit links of all the variables in the WPS Index to the Sustainable Development Agenda’s targets and indicators will facilitate improvements in the WPS Index over time.

Through our continued work on the index, and the update planned for the fall of 2019, our aim is to inform and inspire action by governments, multilateral agencies, development partners, civil society and business, on the important agenda of advancing women peace and security.

[1] These numbers are based on the number of citation reported by Google Scholar 23 January 2018.

[2] Pinker (2011): Pinker, Steven. The better angels of our nature: The decline of violence in history and its causes. Penguin uk, 2011.

[3] Goldstein (2011): Goldstein, Joshua S. Winning the war on war: The decline of armed conflict worldwide. Penguin, 2011.

[4] Gates, S., Hegre, H., Nygård, H. M., & Strand, H. (2012). Development consequences of armed conflict. World Development, 40(9), 1713-1722.

Explore More

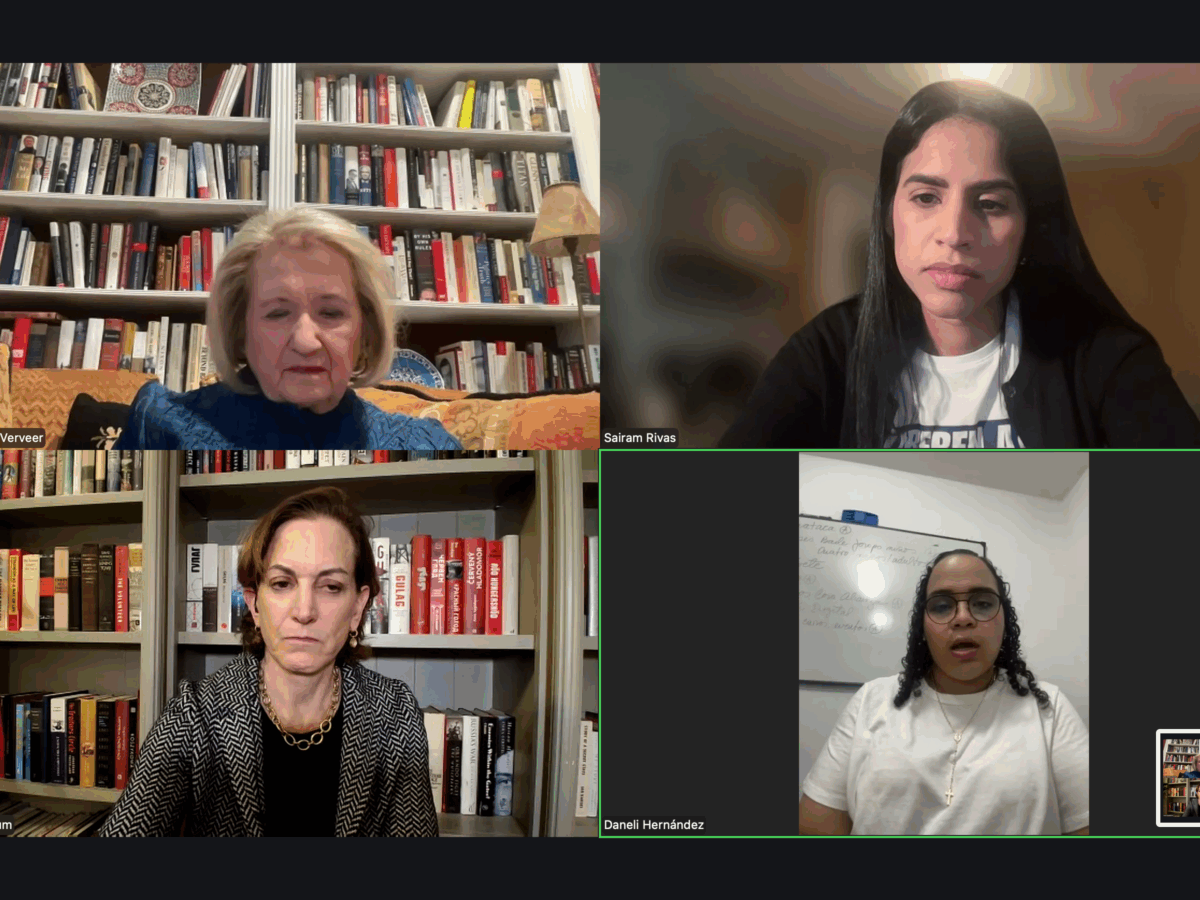

Acclaimed Journalist Anne Applebaum and Women Human Rights Defenders Discuss Implications of…

The people of Venezuela are uncertain about their political, social, and economic…

GIWPS Analysis: The US is Pulling Back from Multilateralism

This week, the White House issued a presidential memorandum announcing that the…

GIWPS Analysis: Iran’s Escalating Political Repression and the Arrest of Narges Mohammadi

Iranian authorities detained 2023 Nobel Peace Prize awardee Narges Mohammadi during a…