The Impact of Conflict on Women’s Access to Education: Spotlight on Burundi

“I was supposed to be in class,” said Betty Sandy Moses, age 32, “but war stopped me.” Betty, who grew up in Sudan before the nation split in two, was forced to quit school at primary five. As she grew older and raised her family, she was eager to give her two children the education that she missed. Joyce Jamba, a Sudanese mother, was left to raise eight children on her own when her husband died. She earned a little money here and there, but it was only enough to cover school fees, uniforms, and supplies for four of her children. Unable to attend secondary school, she still dreams of her own education.

In war-torn countries around the world, thousands of women like Betty and Joyce are denied an education due to protracted conflict, dislocation, and the prevalence of norms or ideologies that discourage education for women. In Burundi, the world’s fourth poorest county still recovering from a brutal civil war that ended a decade ago, it is about to happen again. The current conflict in Burundi, if Rwanda and South Sudan are any example, suggests that women and girls are at heightened risk not only for increased gender-based violence, but also for losing their hard fought educational gains and, ultimately, a pathway to a better life.

President Pierre Nkurunziza’s announcement that he will seek a third term in office threatens to plunge the country into conflict. A violation of the 2005 constitution, the move has both political and ethnic dimensions that impact the entire region. Protestors were killed and many more injured in recent clashes with police. Youth militia are going door-to-door injuring and killing people, and more protests are planned. Aid organizations have ceased activities, and many have evacuated staff. The government closed several radio stations. Police raided their offices and cut off communications. Over 25,000 refugees fled the country, with more leaving every day. President Kagame of Rwanda stated that he will act immediately if ethnic-based violence occurs. The United Nations and human rights groups believe that the country is a high risk for mass atrocities.

Schools are already closing. The Akilah Institute for Women, the only college for women in East Africa with campuses in both Rwanda and Burundi, suspended classes more than a week ago due to increasing violence, with the situation uncertain, it is unclear when the school will be able to reopen. We told the students, whose futures seemed so promising a year ago when the campus first opened, to stay home where they would be safe.

Women and girls in Burundi could lose their chance at an education. It is a risk that impacts all of society. “Evidence has been mounting on the pivotal role that educating a girl or a woman plays in improving health, social, and economic outcomes, not only for herself but her children, family and community,” writes Rebecca Winthrop, who directs the Center for Universal Education at Brookings. Educated girls are less likely to marry early and less likely to contract HIV/AIDs, according to Akilah’s 2010-2014 Impact Report.

Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen was among the first to link the education of women and girls to reduced child mortality. Social scientists at The World Bank connect women’s education to a range of positive social outcomes, including social cohesion and per capita GDP growth.

Girls’ access to primary education around the world has improved, and is almost on par with boys. However, there is a substantial drop-off both at the secondary school level and between secondary and higher education. The result is that young women across East Africa lack the education and skills necessary to find good jobs and achieve financial independence.

“Lower educational attainment places a major constraint on women’s economic participation,” which has stagnated globally, according to The Full Participation Report recently released by the Clinton Foundation. It also impacts self-confidence and aspirations; each year of schooling boosts an African woman’s economic prospects, and results in 10-20% higher wages.

We have learned that global, multilateral efforts in the region are weak-kneed and often ineffective. Regional leaders should prepare to intervene; the African Union should commit to the world that Burundi’s presidential elections will not become a prelude to another civil war, or to genocide. Swift action is needed before it’s too late, for all the women in Burundi, and for the future of the country.

Karen Sherman is the Executive Director of the Akilah Institute for Women and a Senior Associate on Women’s Economic Empowerment at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Commuting to Kigali.

Explore More

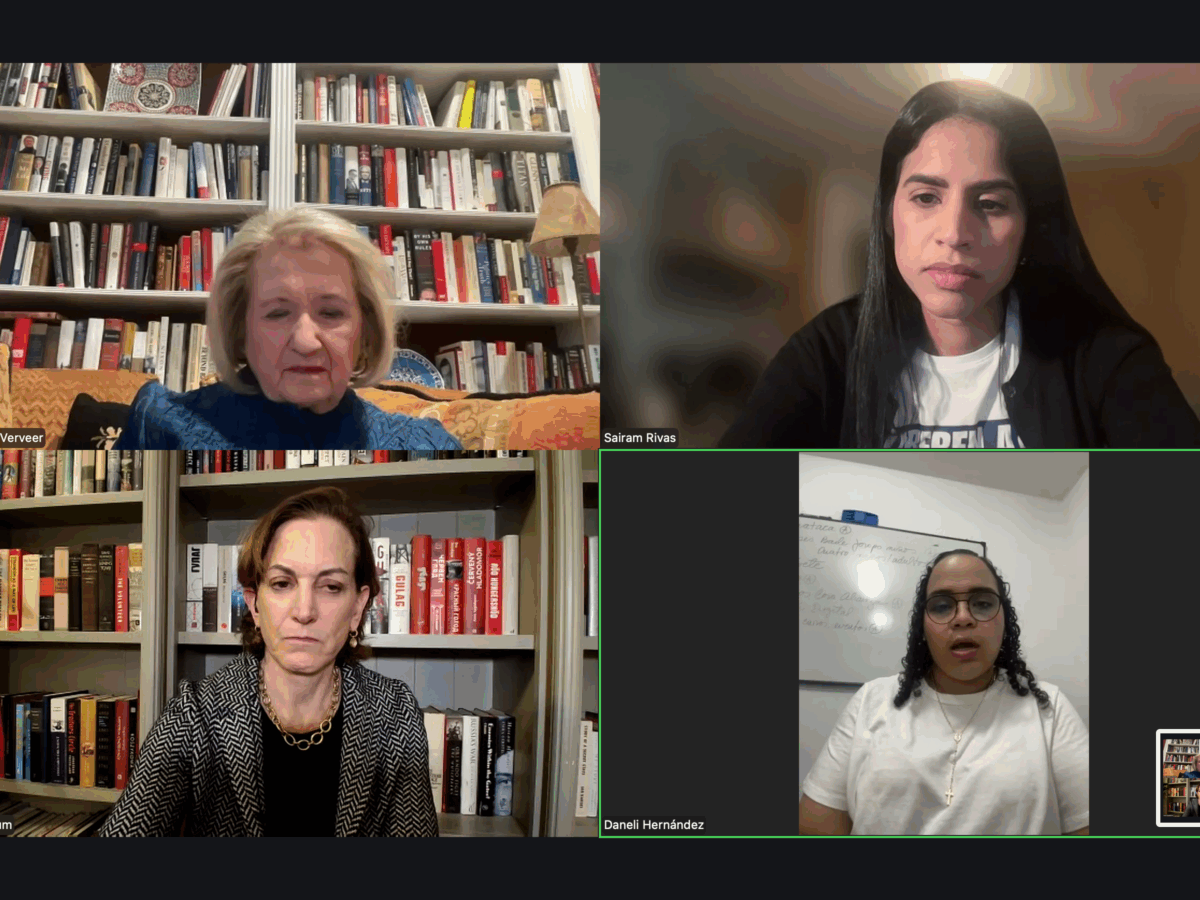

Acclaimed Journalist Anne Applebaum and Women Human Rights Defenders Discuss Implications of…

The people of Venezuela are uncertain about their political, social, and economic…

GIWPS Analysis: The US is Pulling Back from Multilateralism

This week, the White House issued a presidential memorandum announcing that the…

GIWPS Analysis: Iran’s Escalating Political Repression and the Arrest of Narges Mohammadi

Iranian authorities detained 2023 Nobel Peace Prize awardee Narges Mohammadi during a…