What Can the WPS Index Tell Us About Global Risks like COVID-19?

This analysis was supported by the Bank of America Foundation.

In countries around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has quickly revealed systemic weaknesses in myriad national institutions, from health systems to banks and government agencies. Public officials have received increased scrutiny about their administrations’ preparedness and acts in the face of the coronavirus outbreak. Sadly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the countries in the world at highest risk for COVID-19 catastrophe are also those where the status and wellbeing of women is worst.

CARE recently analyzed the INFORM Global Risk Index data, which ranks countries according to their risk of humanitarian crisis using 50 indicators of a population’s exposure to hazards and its access to recovery resources. Their research found that compared to the lowest-risk countries, the highest-risk countries have a three times higher exposure to epidemics such as COVID-19, and also a six times higher risk of a crisis in terms of their access to healthcare.

The set of countries considered at “Very High Risk” of humanitarian crisis by INFORM looked very familiar: Indeed, nearly all the “very high risk” countries (with the exception of Uganda) are in the bottom tercile of the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) Index – produced by GIWPS in partnership with PRIO – which measures the comprehensive wellbeing of women. The “Very High Risk” countries include Somalia, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan, Chad, Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, Niger and Haiti.

The GIWPS research team decided to investigate more systematically the relationship between the WPS Index and the Inform Global Risk Index.

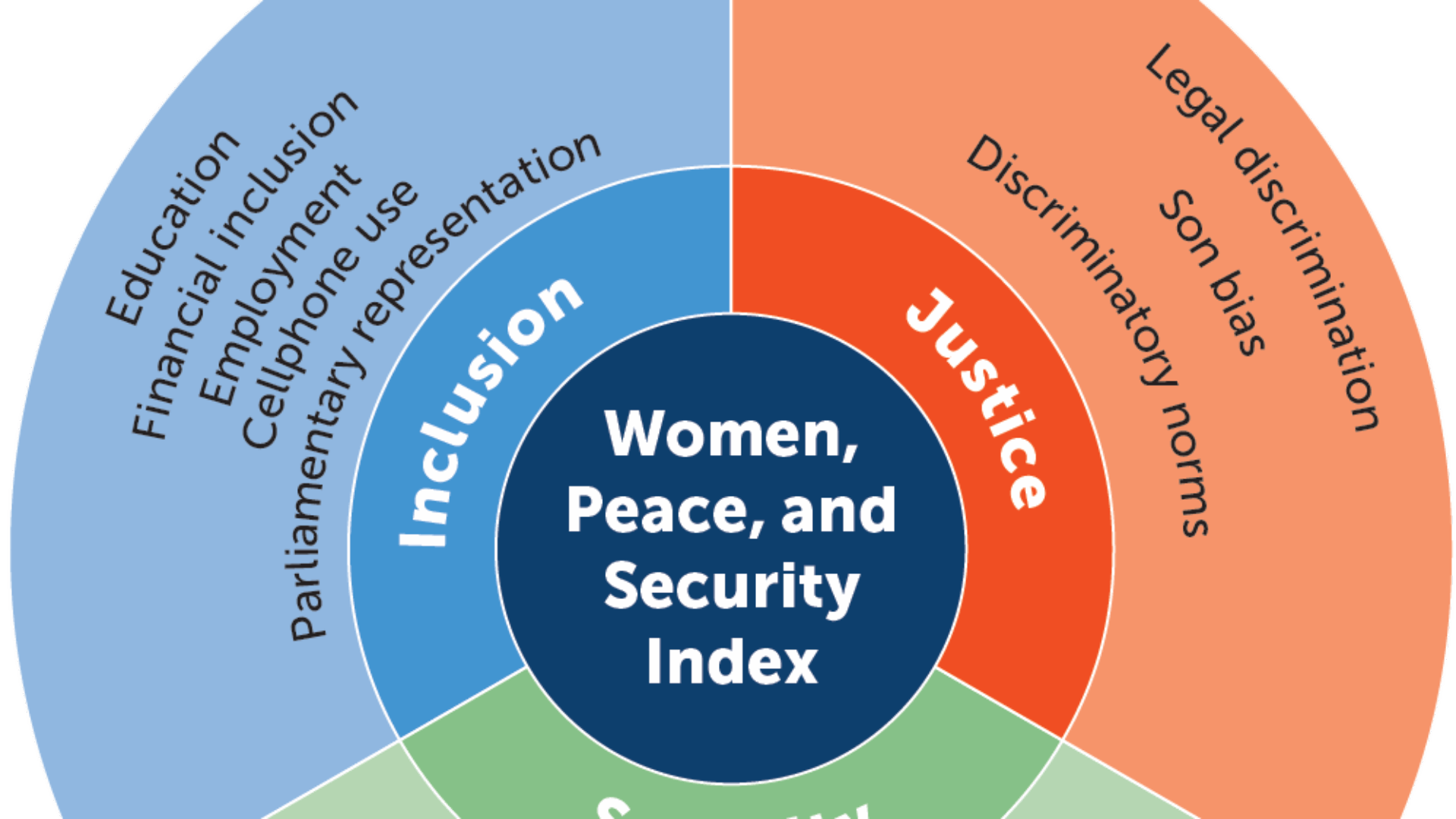

The WPS Index incorporates three basic dimensions of women’s well-being—inclusion (economic, social, political); justice (formal laws and informal discrimination); and security (at the family, community, and societal levels)—which are captured and quantified through 11 indicators, where a higher score indicates better performance. The indicators are aggregated at the national level to create a global ranking of 167 countries.

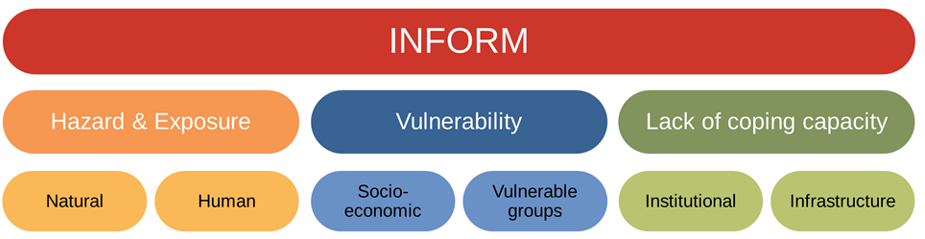

Meanwhile, the Inform Global Risk Index—an initiative of the European Commission—identifies countries at a high risk of humanitarian crisis that are more likely to require international assistance in the event of a disaster. INFORM’s Index is based on risk concepts published in scientific literature and envisages three dimensions of risk: Hazards & Exposure, Vulnerability, and Lack of Coping Capacity. INFORM risk scores are on a scale of 0 (very low) to 10 (very high).

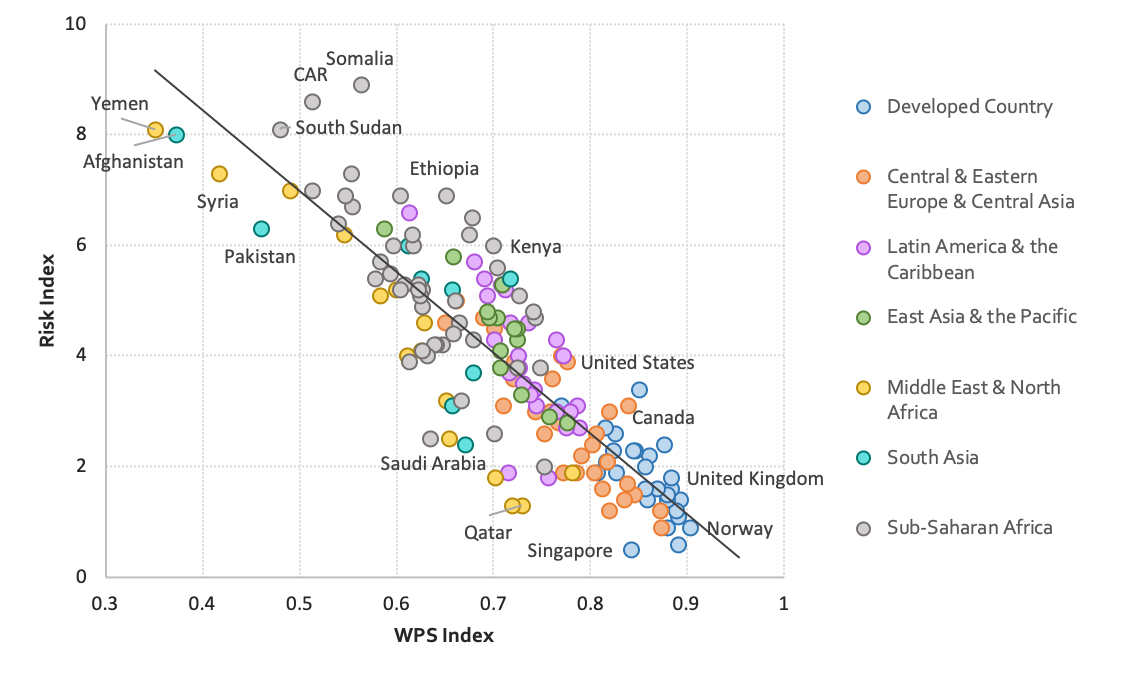

To determine whether there is a relationship between a country’s predisposition to risk and the wellbeing of its female population, we graphed the 2019 WPS Index rankings against the 2019 INFORM Index rankings. The correlation is striking. Indeed, the resulting trend line, which shows a correlation of 0.86, is much stronger than the correlation between the WPS Index and income per capita (0.62).

Figure 1: Countries that Do Better on the WPS Index Have a Lower Risk of Humanitarian Crisis and Disaster

Source: Author estimates based on Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security and PRIO, Women Peace and Security Index 2019/20 report. Index for Risk Management, INFORM Global Risk Index, 2020.

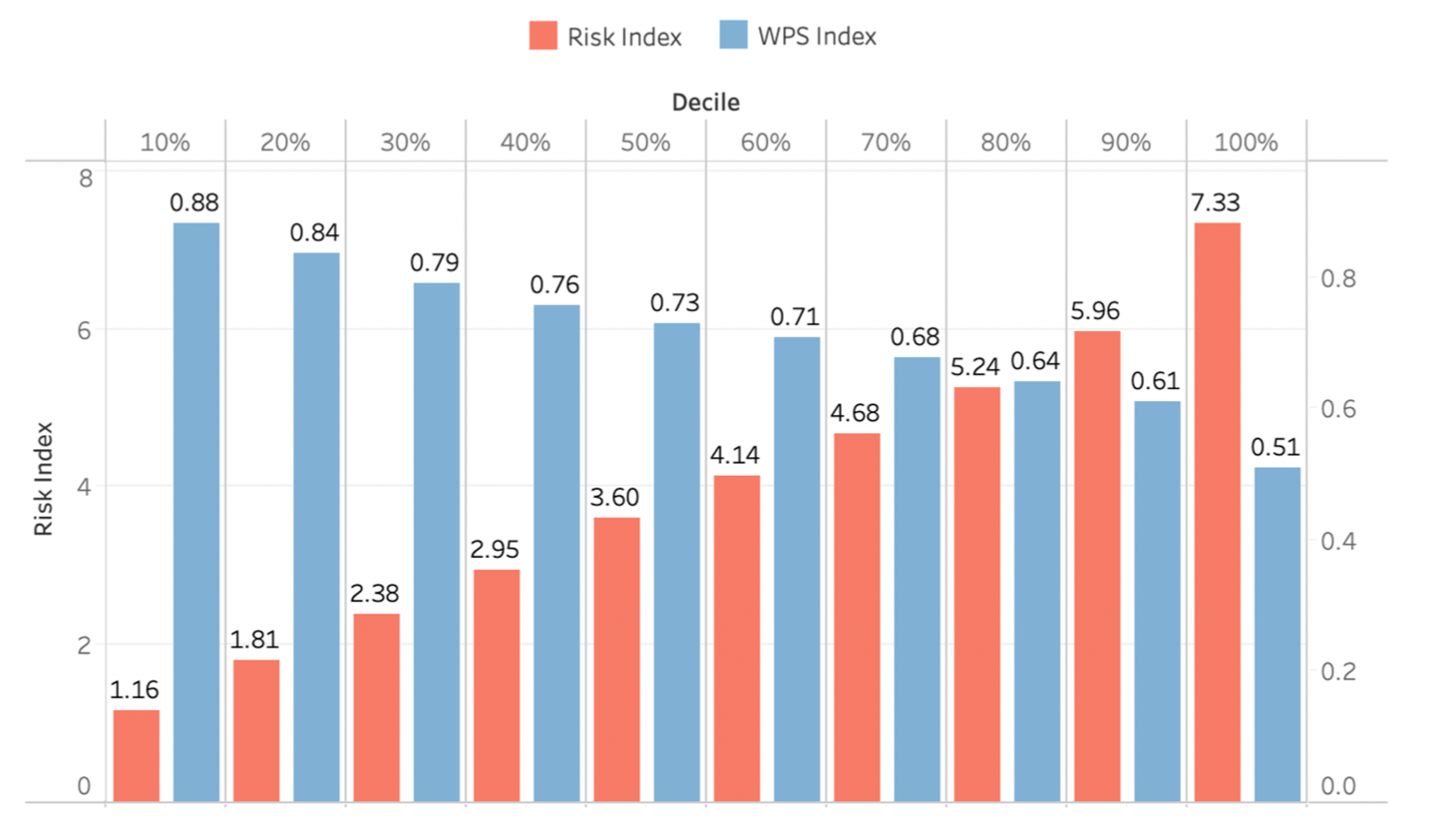

We can see the association clearly in the side-by side comparisons of the index rankings by decile.

Taking the extremes, countries in the bottom decile on the WPS Index average about six times higher risk of humanitarian crisis than countries in the top decile. The bottom decile group consists of Yemen, Afghanistan, Syria, Pakistan, South Sudan, Iraq, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Mali, Libya, Sudan, Niger, Somalia, Sierra Leone and Mauritania.

Figure 2: WPS Index and INFORM Global Risk Index by Decile

Source: Author estimates based on Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security and PRIO, Women Peace and Security Index 2019/20 report. Index for Risk Management, INFORM Global Risk Index, 2020.

Our analysis further suggests that the vast majority (84 percent) of the “very low risk” countries as classified by INFORM are in the top tercile of the WPS Index. Exceptions—very low risk countries that do not perform well in WPS Index—include Bahrain and Kuwait.

At the other end of the spectrum—as noted above—all but one (Uganda) of the “very high risk” countries are in the bottom tercile of the WPS Index.

As CARE points out, the high-risk countries are also over four times (336%) more likely to be at risk of food insecurity, and over three times (210%) more likely to be providing refuge for displaced and uprooted people.

Looking at selected countries, New Zealand is one of the 36 “very low risk countries” as classified by INFORM. It has a low risk in all three dimensions of risk, with the risk from natural hazards somewhat higher. New Zealand also performs well in the WPS Index, with a rank of 14 and balanced performance in different dimensions.

Compared to New Zealand, the U.S. has much higher assessed risks in terms of Americans’ exposure to hazards, vulnerability, projected conflicts, and unprotected people. In the WPS Index, the U.S. (19) comes close to New Zealand in terms of justice and security, but falls behind in women’s inclusion.

Among the “very high risk” countries, both Syria (165) and Sudan (158) are at the bottom of the WPS Index. Although both countries face a major risk on several fronts, Syria faces a higher risk from natural and human hazards, while Sudan lacks the infrastructure capability to cope with risks.

These empirical regularities underline two major points that are especially relevant in the midst of the current crisis, and also in the long term:

First, the extent to which countries are at risk of humanitarian crisis and disaster that would overwhelm national response capacity is strongly associated with the status and well-being of women in the country. While this statistical correlation does not prove causation, the empirical analyses point to key connections—specifically, that nations that extensively exclude women from economic, social, and political life and perpetuate injustice and insecurity for women are both denying and losing opportunities in ways that mean these same countries are often in bad shape when it comes to risks of humanitarian disaster.

Second, and most urgent in the midst of the current pandemic, is that the countries at highest risk for and least prepared to deal with a national emergency are also those where women are generally excluded, denied justice, and face insecurity at home, in the community, and at large.

This shows the major risks of exclusion, injustice, and insecurity for women amidst the risks and hazards created by the COVID-19 crisis, and has important implications for policymaking and development priorities in the recovery and beyond.

Dr. Jeni Klugman is the Managing Director at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security.

Bryan Haiewen Zho (G’20) is a Master’s student in Economics from Ganzhou, China.

Explore More

Global crises in the shadows: Media’s domestic focus

Reassessing Bangladesh’s National Election 2026

The Constitutional Referendum and General Election held on 12 February 2026 was…