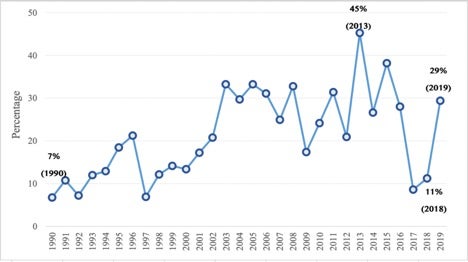

The world seemed to be making slow but steady progress on the inclusion of gender sensitive provisions in peace agreements. References to women and gender had increased significantly since the passing of UNSCR 1325 in 2000: the share of peace agreements with such provisions rose from below 10% in 1990 to 45% in 2013.

However, according to the University of Edinburgh Peace Agreement database, only 11% — 7 out of 62 — of the peace agreements signed in 2018 had references to women, girls and/or gender, similar to 1990 levels. What happened?

Gender provisions in peace agreements can range from land rights for women (Darfur), to quotas for political representation (Burundi and Nepal), to measures against perpetrators of sexual violence (Colombia). We investigated the most updated version of the University of Edinburgh Peace Agreement database, which contains 1823 peace agreements between 1990 and the end of 2019 and defines peace agreement as “formal, publicly available documents, produced after discussion with conflict protagonists and mutually agreed to by some or all of them, addressing conflict with a view to ending it.”

Fortunately, there was a rise again in 2019, when 29% of agreements had gender provisions. But this is still below the earlier peak of 45% in 2013, and falls short of the UNSCR 1325 commitment that all peace agreements be gender sensitive.

Figure 1: Proportion of peace agreements with provisions on women, girls and gender issues (1990–2019)

Source: Adapted fromE/CN.6/2020/3 report, p.78

As 2020 marks the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Conference on Women and the 20th anniversary of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (UNSCR 1325), we need to understand why such a regression emerged, and what can be done moving forward.

We know from earlier research that variables such as conflict duration, third-party role, civil society engagement, and women’s participation in peace processes increase the likelihood of having gender provisions in peace agreements (Bell and O’Rourke, 2010; True and Riveros Morales, 2018; Anderson, 2016).

At the same time, Jacqui True and Yolanda Riveros Morales found that the likelihood of achieving a gender-sensitive peace agreement between 2000 and 2016 was higher when women’s civil society participation was significant, and when women participated in Track I and Track II peace processes.

Do these factors explain the recent drop in gender provisions? We undertook further research –comparing the years 1990, 2013, and 2018 – to try to identify what had changed since the peak year of 2013. Our preliminary results, which will be elaborated in a forthcoming GIWPS research paper, suggest the following:

- The relatively high proportion of ceasefire agreements – 29% of the 2018 agreements were ceasefire related –might partly explain the lack of gender provisions overall because ceasefire agreements focus on stopping the fighting between the parties to allow for peace negotiations and tend not to address substantive issues.

- Fewer women were listed as parties and third parties in 2018. Our findings show that the number of women as parties to the agreement in 2018 is lower (11%) than in 2013 (19%) and in 1990 (16%). The more women listed as parties or third-parties, the more likely that agreements have gender provisions. In 2013, women were also listed as third parties more than in “low” years (17% compared to 10% in 2018 and 2% in 1990).

- Most of the agreements in 2018 were in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (52%). We know that women in this region face major challenges, as reflected in GIWPS/PRIO’s Women, Peace and Security Index. For instance, the regional average in terms of women’s parliamentary representation is 17% compared to 23% in Sub-Saharan Africa and 28% in Latin America. In 2013, agreements were mostly in Africa (50%) and Asia (33%) compared to 35% and 6% respectively in 2018.

- Shorter duration of conflict. Anderson (2016) found a positive correlation between provisions on women’s rights in peace agreements and longer conflict duration. This is partly due to more effective women’s groups advocacy over time and deeper changes to gender roles during conflict. During the peak year, 2013, we found that 57% of the agreements were related to conflicts that had been running for more than 16 years compared to 18% in 2018 and 32% in 1990. The majority of 2018 agreements (65%) aimed at resolving protracted conflicts (between 6 and 10 years).

- Less active UN peacekeeping presence. UN peacekeeping presence indicates high international involvement and can also facilitate negotiations between warring parties, such as local conflict resolution in the Central African Republic. Bell and O’Rourke (2010) found that the rise in gender provisions was more marked among agreements in which the UN had a third-party role. Our findings show that there was active UN peacekeeping in 24% of the 2018 agreements – which is less compared to 33% in 2013 and might partly explain the decline in gender provisions.

- The 2020 UN Secretary General report suggests that the decline in gender provisions is partly due to the local and early stage nature of the 2018 agreements, because women are largely excluded from early stage dialogues. However, we find that 42% of the 2018 peace agreements had previous agreements reached as part of the same peace process – compared to 55% in 2013 and 41% in 1990. Moreover, only 19% of the 2018 agreements are pre-negotiation agreements. This suggests that the early stage nature of agreements does not explain the drop in gender provisions.

In 2019, there is a welcome trend reversal, with 29% of agreements having gender provisions (5 out of 17). Women were also parties to 41% of agreements reached in 2019, a major improvement on the two preceding years.

What characterized the agreements reached in 2019?

- A majority of Africa-based agreements. 47% of the agreements were in Africa, 29% in MENA, and 18% in Europe. Among the agreements with gender provisions, none were in MENA – 80% were Africa-based and the rest in Eurasia.

- Recent and protracted conflicts. 41% of the 2019 agreements aim to resolve recent conflicts between 0 and 5 years and 47% are for protracted conflicts between 6 and 10 years. Among agreements with gender provisions, 60% seek to end protracted conflicts between 6 and 10 years.

- Process stage and agreement type. Overall, 65% of the 2019 agreements had prior agreements reached as part of same peace process. 53% of these agreements address substantive issues (partial or comprehensive), and 33% of them have gender provisions.

- Active UN peacekeeping and accords with gender provisions. Half of 2019 agreements have active UN peacekeeping happening and 80% of those with gender provisions have UN peacekeeping going on.

What can be done moving forward?

First, and most important, we cannot assume that progress will continue and the international community should be vigilant against backlash. The UN and third parties to peace negotiations need to have more women mediators in their own delegations – women are still far too few in third party delegations – and to strongly advocate for gender provisions.

While the MENA region is dealing with major conflicts in Syria, Libya, and Yemen, the risk of women’s exclusion is also highest. This means that international actors in those conflicts must strongly advocate for women’s effective inclusion in negotiations – both among third-party delegations and warring parties, since that has both intrinsic and instrumental value.

Some of the implications cannot be directly addressed – most notably conflict duration. However, women’s inclusion early on in peace processes may increase the number of gender-sensitive agreements aiming to end conflicts that have been running between 0 and 5 years, before they become protracted.

More generally the inclusion of local civil society, especially women’s groups, and providing support to enable effective participation, is particularly critical to building and sustaining peace.

Agathe Christien is the 2019-2020 Hillary Rodham Clinton Research Fellow at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security. Her research interests and expertise include women’s involvement in peace processes and peacekeeping, countering violent extremism, and international migration.