As COVID-19 continues to spread swiftly around the world, governments and public health officials are urging populations to follow aggressive prevention measures. For individuals experiencing homelessness, however, some of these measures are unrealistic prospects. For example, one of the main components of the U.S. response to the coronavirus outbreak has been shelter-in-place, but it is beyond the bounds of possibility for the 567,715 people experiencing homelessness in the United States to follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) most basic directive: “Stay Home.”

Data from the 2019 Point-In-Time (PIT) Count indicated that approximately two-thirds (63%) of people experiencing homelessness in the United States were staying in shelters, and more than one-third (37%) lived in places not meant for human habitation such as cars, tents, or parks. Such precarious living conditions, when paired with compromised immune systems, lack of access to adequate medical resources, and inability to self-isolate, put individuals experiencing homelessness at a significantly higher risk of contracting, transmitting, and dying from COVID-19.

A recent observational study conducted at an urban safety-net hospital in Washington State found that the rates of respiratory diseases, which are a major risk factor for coronavirus, are particularly high among homeless individuals. Throughout the course of the study, 32% of the people hospitalized for respiratory diseases at the aforementioned hospital were individuals experiencing homelessness, compared to 6.5 % of all patients hospitalized. Another research study published last month estimates that more than 21,000 individuals experiencing homelessness in the U.S. could become hospitalized with COVID-19, and more than 3,400 of this population could die from the disease.

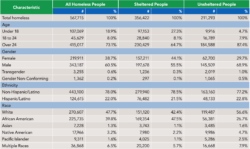

Demographic Characteristics of People Experiencing Homelessness in the United States in 2019

Source: https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2019-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

Source: https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2019-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

In response to the impact of the public health threat on individuals experiencing homelessness, governments and communities around the world have developed and implemented a range of prevention and response strategies that include sheltering homeless residents at sports stadiums, altering the structure of existing facilities to accommodate social distancing, and providing housing alternatives (motels, dormitories, hotels) to those at particularly high risk of contracting the disease. While these interventions are salutary, there is still a greater need for permanent solutions to housing as well as gender-sensitive responses.

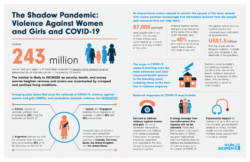

The Case of Women and Girls at Risk of or Experiencing Homelessness During COVID-19

Although women and girls experience homelessness at a lower rate than men, their experience of homelessness and housing insecurity differs significantly from that of their male counterparts. Unlike men, women and girls’ vulnerability to homelessness and housing insecurity is highly associated with factors related to domestic violence, child marriage, lack of access to high-wage occupations, human trafficking, and lack of access to childcare. Women from minority groups are in an even more precarious position, owing to their intersectional identities and dynamics that intensify their experiences of discrimination. As a result, it is not surprising that quarantines and mandatory lockdowns imposed by governments to curb the spread of COVID-19 are deepening already-entrenched gender inequalities and disrupting the lives of women and girls experiencing homelessness in a disproportionate manner.

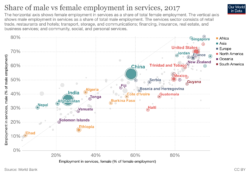

Housing and employment are inextricably linked, and women-dominated industries are being significantly impacted by the economic slowdown as businesses are forced to close due to COVID-19. Global data indicate that 58% of services industry employees are women, and that sector has been one of the worst hit by the pandemic. While economists are only beginning to quantify the short and long-term economic impacts of COVID-19, it is clear that it has changed the lives of countless of women around the world and that these women will experience a greater economic insecurity as a consequence of sudden job losses. The implications of such precarious economic circumstances for women and girls experiencing homelessness include an interruption of their path to economic self-sufficiency and, consequently, housing stability. Experts also expect to see a significant increase in the number of women and girls seeking shelter in communities that do not have an eviction moratorium in place, a trend that will continue to grow post-pandemic. As a consequence of gender-based discrimination and other discriminatory practices that promote the subjugation of girls and women, another potential economic impact of COVID-19 is an increase in the number of homeless survivors of child/forced marriage. As seen during the Ebola Outbreak, some underprivileged families who have lost their source of income during COVID-19 may see child marriage as a way out of poverty.

The health crisis has also exposed horrendous preparedness shortcomings in institutions that were created to support and protect homeless survivors of domestic violence. For some shelter residents, COVID-19 has meant going back to their abusers and facing greater risk of violence or death. In the United States, approximately 41% of female domestic violence survivors sustain a physical injury from their abusers, and about 1 in 6 homicide victims are killed by their intimate partners. In South Africa, a woman is killed every four hours.

A survivor’s decision to return to her abuser amid COVID-19 seems to be largely influenced by limited access to resources and fear of the spread of the virus within overcrowded shelters, which have been struggling to meet the soaring demand in domestic violence services since the beginning of the outbreak. Victims’ rights advocates attribute the upsurge in the number of domestic violence cases to the intersection of mandatory lockdowns, disconnection from social support systems, and extreme financial distress. These observations echo some of the concerns raised by Anita Bhatia, Deputy Executive Director of the United Nations Women. In an interview with TIME, Bhatia shared that “the very technique we are using to protect people from the virus can perversely impact victims of domestic violence.” She added that while measures such as social distancing and isolation have some merits, it is important to recognize that they also provide “an opportunity for abusers to unleash more violence.” The facts speak for themselves: In Tunisia, there has been a fivefold increase in the number of domestic violence cases during the first five days of quarantine, and in France, domestic violence increased by 30% in just one week in areas under movement restrictions. Similar increases in domestic violence cases have been documented during past pandemics such as Ebola.

Less visible, but equally important, is the impact of COVID-19 on period equity. Like homelessness, the issue of period poverty predates the pandemic. Many women and girls experiencing homelessness have struggled to access menstrual hygiene products and have relied heavily on charitable organizations to meet their personal, yet essential needs. Surprisingly, in many countries including the United States, homeless shelters are not required to provide menstruators with period products. This means that the rate of period poverty among women and girls experiencing homelessness is likely to increase with the crisis as several organizations serving homeless menstruators are either closed to the public or have limited supplies. PERIOD, an organization that has distributed over 200,0000 period products since the beginning of the pandemic, announced just recently that its stock of menstrual supplies was running low due to an increased demand. Under these conditions, women and girls experiencing homelessness are further exposed to the medical and psychological impacts of not using period products, using them for a longer period of time than recommended, or reusing them. For women and girls experiencing unsheltered homelessness, the lack of access to public showers and adequate sanitation adds another destabilizing burden to already tenuous conditions.

Call to Action

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security acknowledges the disproportionate impact of conflict on women and girls and calls for their inclusion as equal partners in all efforts to maintain peace and security. Two decades after the adoption of Resolution 1325, its principles are more relevant than ever and can inform the global response to COVID-19.

The challenges faced by women and girls experiencing homelessness suggest that progress toward inclusive and gender-sensitive responses to pandemics has been slow.

Homelessness is a public health issue, and safe housing is a human right. For women and girls experiencing homelessness during COVID-19, access to adequate and safe housing is the difference between life and death. Hence, governments must take immediate and gender-sensitive actions to protect this vulnerable population from the devastating effects of the pandemic.

Taking gender-sensitive actions includes incorporating gender analysis into preparedness and response efforts, developing and implementing policies that strengthen the safety of women and girls during outbreaks, and most importantly, providing women and girls with lived experiences of homelessness meaningful and purposeful opportunities to inform and shape all levels of response planning and implementation.

A key to achieving the desired impact of gender-sensitive response to pandemics—in this case, the protection of women and girls experiencing homelessness during COVID-19 and beyond—is the collection and dissemination of sex-disaggregated data. Relatively little is known about the impact of pandemics on women and girls experiencing homelessness, and sex-disaggregated data could help monitor vulnerability and risk trends among this population. In addition to informing future policy decisions and response strategies, sex-disaggregated data can help strengthen the preparedness capacity of communities in which women and girls experiencing homelessness live. To undo the damage of sidelining women and girls, governments and communities must also recognize that sex-disaggregated data can be used to reinforce systems and practices that have discriminated against them in the past.

Given the intersection of housing and employment and the economic consequences of COVID-19 on women and girls, an effective response to the pandemic must build on the foundational work of gender equality activists to improve employment and economic opportunities for women and girls experiencing homelessness. Additionally, increasing the supply of affordable housing must be priority.

Last week, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres wrote on Twitter, “I urge all governments to put women’s safety first as they respond to the pandemic.”

Putting the safety of women and girls experiencing homelessness first means treating them with respect and dignity and ensuring that they have a safe place to call home and access to health services and menstrual products at all times—and preeminently in times of crises. Women and girls experiencing homelessness should not be left behind in the pandemic’s wake, and community members can play a big role in ensuring that they are supported. Every single action can make a big difference, whether it is donating to local shelters, looking out for a neighbor experiencing domestic violence, or providing those in need with period products, food, and shelter. Health crises can become events that bring about changes in policies and practices that affect the most vulnerable members of our communities. COVID-19 may be our only opportunity to achieve positive peace by putting the safety of every woman and girl experiencing homelessness first.

Eliane Lakam is an alumna of Georgetown (C’18) and a recent graduate of Harvard University, where she completed graduate studies in International Education Policy. She is currently a Fellow at the Baltimore City Mayor’s Office of Homeless Services. @ElianeLakam.