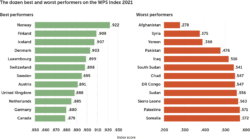

In 2021, Pakistan again scored poorly on the WPS Index, ranking 167 of 170 countries, behind Iraq and South Sudan. Between 2017 and 2021, Pakistan regressed on two measures of inclusion—women’s mean years of schooling and rates of paid employment. Pakistan’s ranking on the WPS Index is 42 places below its ranking on GDP per capita.

Pakistan has adopted several key international commitments to women’s rights, including the Beijing Platform for Action, the 1996 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the Sustainable Development Goals. Federal and provincial governments have gradually legislated legal reforms, most notably the Women’s Protection Bill (2006) and the 2016 Criminal Law Act outlawing rape. While those steps are important, implementation remains weak, and Pakistani women’s rights advocates face continuing opposition from political and religious forces.

Pakistan has achieved major reductions in poverty over the past 20 years, but stark inequality persists both within and across its four federal provinces. In all provinces, there are huge gaps between the political elite and ordinary citizens, between urban and rural populations, between rich and poor, and between women and men.

Large economic disparities characterize Pakistan. Punjab, with 110 million people, and Sindh, with 48 million, are the main drivers of Pakistan’s economy, with the country’s largest cities and the main areas of agricultural activity. Balochistan, with 12 million people, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), with 31 million, are less prosperous and tend to receive less federal fiscal support. Balochistan and KPK have also experienced protracted conflicts, political violence, and military operations, which have limited economic and social development. While KPK’s economic situation has improved since 2012, Balochistan, the largest province in size and the smallest in population, lags behind the rest of the country in human development.

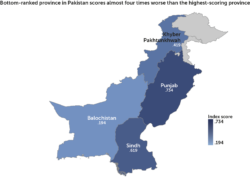

Provincial index scores ranged widely across Pakistan, from .734 for Punjab to .194 for Balochistan. The rankings on the provincial WPS Index mirror those for income and poverty. Punjab was the best-off, with the lowest reported rate of income poverty—32 percent—while Balochistan’s poverty rate approached 60 percent.

Performance on inclusion was alarmingly low across Pakistan’s provinces. Rates of female employment hovered around 10 percent in Balochistan, KPK, and Sindh, which would rank those provinces with the world’s bottom four countries on the global WPS Index. Agriculture was the country’s largest source of employment, but women in agriculture were more likely than men to be unpaid family workers and unprotected by labor laws in any province but Sindh. Only 16 percent of women in Balochistan had a cellphone, 11 percentage points lower than women in South Sudan, the country with the world’s lowest women’s cellphone use rate.

On average, girls had much less access to education in Pakistan than boys—mean years of schooling was 3.9 for women and 6.4 for men. Only in Punjab did even half of women (52 percent) complete at least primary school, and rates were as low as 19 percent in Balochistan and 30 percent in KPK. In all provinces, 10 percent or less of women have completed secondary school.

Although women have been active in Pakistani politics since independence, their formal parliamentary representation remains limited. Almost two decades ago, President Pervez Musharraf introduced a 17 percent quota for women in national and provincial assemblies. Current women’s parliamentary representation in provincial assemblies ranges between 17 and 20 percent, just meeting the modest quota.

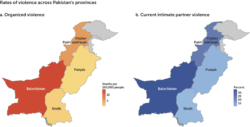

As elsewhere in the world, two key aspects of women’s security—organized violence and current intimate partner violence—are closely related across Pakistan. Women in the provinces with the highest rates of organized violence also face the highest rates of current intimate partner violence, underlining the amplified risks of violence at home in the vicinity of conflict. Balochistan had the highest rates of both—organized violence was at 14 deaths per 100,000, and 35 percent of women had experienced intimate partner violence in the past year.

Pakistan’s provinces are large. Provincial averages conceal considerable diversity, especially between better-off urban areas and more remote areas. Pakistan has the highest urbanization rate in South Asia, estimated in 2017 at 36 percent and expected to increase to 50 percent by 2025. Sindh is more than 52 percent urban. In Pakistan, as elsewhere, urban areas tend to be more prosperous economically, with better access to education and health services. But inequality is also high in urban areas, contributing to grievance and conflict. Inequality in urban centers is most pronounced in levels of income and education.

Provincial profiles

Punjab emerged as Pakistan’s highest-scoring province, with a provincial WPS Index score comparable to Brazil’s score on the global WPS Index. Punjab scored above the national average on inclusion, justice, and security, traceable in part to high rates of urbanization. The province had the fewest deaths due to organized violence, around a quarter of the national average, but was still marked by political violence, including riots, protests, and attacks by militant groups. Punjab had a largely agrarian economy with economic stagnation in more rural areas along with high, and worsening, income inequality traced to urbanization.

Sindh performed around the national average on women’s education and discriminatory norms, but below average on employment, intimate partner violence, and organized violence. Sindh had the highest levels nationally of women’s financial inclusion, at 25 percent, and participation in household decision making, at 46 percent. But urban–rural differences were stark, with 15 percent of urban women completing secondary education, compared with only 2 percent of rural women.

Urban inequalities are also prevalent in Sindh. Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and financial capital, hosts some of South Asia’s largest slums and informal settlements. Despite substantial income from wages and salaries and from property, Karachi has experienced recurrent waves of ethnopolitical, sectarian, and militant violence.

KPK and Balochistan scored poorly on virtually all the indicators in our provincial WPS Index. In KPK, women’s employment stood at 12 percent, financial inclusion at 17 percent, cellphone use at 37 percent, and participation in domestic decision making at 19 percent. Balochistan, bottom ranked of the provinces, experienced extensive deficits in women’s social and economic inclusion: women’s employment was a meager 8 percent, financial inclusion was 13 percent, and cellphone use was 16 precent. Balochistan also scored poorly on women’s participation in decision making (10 percent) and had a high level of son bias—approximately 111 boys were born for every 100 girls, similar to the world’s three highest country rates (Azerbaijan, China, and Viet Nam). Only 5 percent of girls in KPK and 4 percent in Balochistan completed secondary education.

Provincial variations in threats of violence at home and at large

Balochistan and KPK had the highest rates of intimate partner violence in Pakistan—Balochistan at 35 percent and KPK at 24 percent. Women’s rights groups report that gender-based violence increased during the pandemic, when women were forced to stay at home. Human rights groups report more than 1,000 “honor killings” of women annually.The two provinces are also marked by protracted conflict, causing high levels of civilian casualties and displacement.Balochistan has suffered from inadequate numbers of qualified teachers and deficient public transportation, severely limiting access to public services such as healthcare.

Even more stark is the violence faced by women in some of Pakistan’s federally administered territories and so-called special regions, which are not official provinces. It has been reported that in those regions, 56 percent of girls experience gender-based physical violence by the age of 15. More than 95 percent of women in those regions believe that their husbands are justified in beating them during domestic disagreements or as punishment.