Afghanistan’s 34 provinces range in population from about half a million in Badghis to more than 5 million in Kabul. The population is 74 percent rural, though urbanization has been rapid over the past decade. Rural–urban disparities in income, education, and access to public services are large and growing. In Afghanistan, one of the world’s poorest countries, an estimated 40 percent live in poverty.

Afghanistan is ethnically, linguistically, and religiously diverse, with political mobilization and conflict often reflecting these divides. Pashtuns are the largest ethnic group (38 percent), followed by Tajiks (25 percent) and Hazaras (19 percent). Pashtuns generally observe more conservative gender norms than the Tajiks and Hazaras, constraining women’s status and rights.

Efforts to advance the position of Afghan women and girls received much attention after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, and opportunities for education, employment, and political representation improved. For example, by 2018, 83 percent of Afghan girls had enrolled in primary school, and by 2019, more than 1,000 Afghan women had started their own businesses, two activities previously prohibited under the Taliban. However, mean schooling for Afghan women was still alarmingly low, at just two years. The collapse of the Afghan government and rise of the Taliban in August 2021 clearly jeopardize past progress for Afghan women and threaten reversals in access to rights and justice.

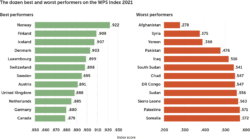

Despite some modest gains prior to recent events, progress had not been linear, and the country still lags significantly behind others. In the 2021 global ranking of 170 countries on the WPS Index, Afghanistan scores worst, falling in relative and absolute terms since 2017. On several indicators—women’s cellphone use, parliamentary representation, and perceptions of community safety—Afghanistan has regressed, while much of the rest of the world has improved. On all aspects of security in the global index, Afghanistan’s score is the worst in South Asia and among the worst in the world. This record underscores the devastation of women’s status and opportunities wreaked by ongoing conflict.

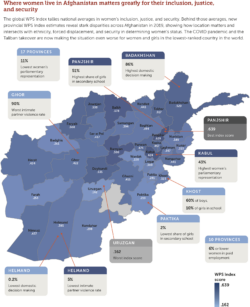

While Afghanistan ranked worst in the world on the 2021 global WPS Index, there were major disparities within the country. Millions of women living in some provinces fared far much worse than others. The subnational index scores ranged from .639 in Panjshir to .162 in Uruzgan. The widest gaps were in organized violence, ranging from about 7 deaths per 100,000 people in Bamyan to 301 in Uruzgan. The narrowest gaps were in the rates of son bias.

Better performers

Panjshir province, northeast of Kabul, leads the Afghan subnational index, doing relatively well on the security dimension—though the rate of organized violence in the province, 8.8 fatalities per 100,000 people, is still at a level similar to those among the worst 10 countries in the world. Panjshir’s rate of current intimate partner violence—reported at 23 percent—was about half the national average but double the global average and among the worst in the world. Girls’ secondary education attainment in Panjshir was 51 percent—double the national average but still far short of the 60 percent average estimated for South Asia. About 7 of 10 women in the province participated in household decisions about healthcare, major purchases, and visits with relatives.

The capital Kabul ranked second best in Afghanistan. It outperformed the national average on girls’ education, exposure to mass media, parliamentary representation, discriminatory norms, intimate partner violence, and organized violence. While girls’ access to education was highest in Kabul and Panjshir, levels of women’s employment remained low in both provinces, recalling patterns in the Middle East and North Africa.

Badakhshan, Balkh, Bamyan, Daykundi, Faryab, Jowzjan, Parwan, and Takhar, located in the central and northeast regions of Afghanistan, have majorities of ethnic Hazara, Tajik, and Turkmen populations. All exceeded the national average on education and women’s participation in household decision making. Daykundi stood out, with the highest rate of female secondary school enrollment, at 45 percent, and the second highest rate of participation in domestic decision making, at 74 percent.

Worst performers

Afghanistan’s lowest-ranking provinces are mainly in the southeastern areas, where conflict has been protracted. Nine of the ten lowest-performing provinces—Badghis, Logar, Kandahar, Khost, Kunar, Paktika, Paktia, Uruzgan, and Wardak—are Pashtun-majority. These provinces were marked by high rates of organized violence and intimate partner violence, widespread acceptance of wife beating (between 67 and 97 percent), and very low levels of women’s participation in domestic decision making (between 3 and 21 percent).

Ranking worst in the country, Uruzgan scored poorly across the board, reporting the highest level of organized violence (301 fatalities per 100,000 people), very low levels of girls’ secondary school attendance (3 percent), few women in paid employment (6 percent), and very little exposure to mass media (only about 1 woman in 20 watched television at least once a week). The province also had one of the smallest proportions of female legislators at 11 percent, compared with the national average of 27 percent.

Ghazni province is an exception among the southeastern provinces. Levels of insecurity were extremely high (198 battle deaths per 100,000 population and a 65 percent rate of current intimate partner violence), and the share of women in paid employment was only 7 percent. Yet, Ghanzi had one of the highest provincial rates of girls’ secondary education enrollment, at 39 percent—good by Afghan standards, but still very low compared with regional and global averages.

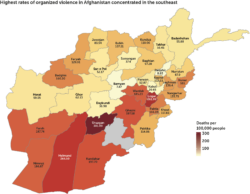

Organized violence and intimate partner violence

The ongoing conflict in Afghanistan has been among the world’s deadliest. Organized violence was high across the country, with the worst-affected provinces clustered in the south and southeast (figure 3.7). And attacks by the Taliban, sectarian and ethnic violence, and criminal violence associated with the war and drug economy were frequent.

The return of the Taliban is widely expected to further unravel progress Afghan women have made and worsen the situation for women around the country. In mid-2021, there were already signs of oppression, as the Taliban reportedly sent home women professors and students in Herat and were forcibly marrying women to Taliban soldiers. A Taliban spokesman has warned that, for their own safety, women should not go to work.

Many are calling on the United States and allies to evacuate Afghan women activists, support relocation efforts, and expedite refugee visas for those displaced. Organizations like the International Rescue Committee are working to provide Afghan women and girls access to education and critical healthcare.

High rates of violence in the home compounded the security threats facing women. Nationwide, 35 percent of Afghan women experienced intimate partner violence in the past year, and rates exceeded 84 percent in Ghor, Herat, and Wardak provinces—higher than those in any country in the global WPS Index. Gender-based violence reportedly increased during the pandemic, as did women’s suicides and attempted suicides.

Limited opportunities for Afghan women in education and employment

The results revealed especially large provincial disparities in women’s access to education and paid employment. Despite the Taliban’s ban, girls’ education was a priority for the government and its international supporters. In 2015, 1 girl in 4 attended secondary education—marking gains since 2001—but the vast majority of girls were still excluded. Girls’ access to schooling ranged from 45 percent in Daykundi to a mere 2 percent in Paktika, with the lowest rates concentrated in the southeast. There were also major gender gaps: for example, about 6 boys in 10 were in secondary school in Khost, but only 1 girl in 10. With the Taliban back in power, girls’ education is under severe threat.

Few Afghan women were in paid employment, due to both ongoing conflict and adverse norms. Female employment rates were under 10 percent in the insecure provinces in the southeast but around 20 percent in the relatively stable provinces of Faryab, Jowzjan, Nuristan, Samangan, and Sar-e Pol. Cultural norms emphasizing women’s domestic and caregiver roles limit women’s opportunities outside the home, not only in rural areas but also in Kabul, where only about 1 woman in 17 was in paid employment. If Kabul were a country, it would rank second worst on this indicator worldwide, above only Yemen.

The post-2001 political order set an ambitious agenda for women’s political participation, introducing a 27 percent quota for women’s parliamentary representation—the highest in South Asia. Although that quota was met nationally, women’s representation was highly uneven across provinces. Kabul led with 43 percent female parliamentary representation, but 25 provinces did not meet their target, which was lowered from 25 to 20 percent in 2013—a setback for women’s rights. And although women’s formal representation rose, it is unclear whether women’s substantive influence actually increased. Again, the prospects for women’s representation in government and decision making are under severe threat.

The Afghan government, with international support, developed comprehensive legal frameworks for securing women’s rights, political participation, and inclusion in the peace process. Progress included securing women’s rights in the constitution (2004), enacting the Law on Elimination of Violence against Women (2009), and launching the National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security in 2015. Yet, only 10 percent of participants in peace processes were women, and they were not included in 61 of 76 talks between 2005 and 2020.

The national government faced significant challenges in implementing the National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security, including insecurity, budget and capacity constraints, and lack of interagency coordination. The donor community was expected to fund implementation, but it is unclear how much support materialized. The future of the National Action Plan is in serious doubt.

With the Taliban gaining control of the country in August 2021, the future of women’s rights is in severe jeopardy in a setting where discrimination and violence against women is already pervasive, especially in the southeastern provinces. Girls’ access to school, now ensured around much of the world, even in the poorest countries, was denied to most Afghan girls under the previous Taliban regime. As Afghanistan continues to attract attention on the global stage, a special focus on the women and girls living in provinces that have been left behind will be critical. Our results—though not capturing trends over time or demonstrating what would have happened without these reforms—suggest that Afghanistan has far to go to protect the basic rights of women across the country.