Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, news articles have speculated that countries with female political leaders have fared better than comparable countries led by men. New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern was touted as the world’s greatest leader, and other female leaders like Germany’s Angela Merkel and Finland’s Sanna Marin also drew praise.

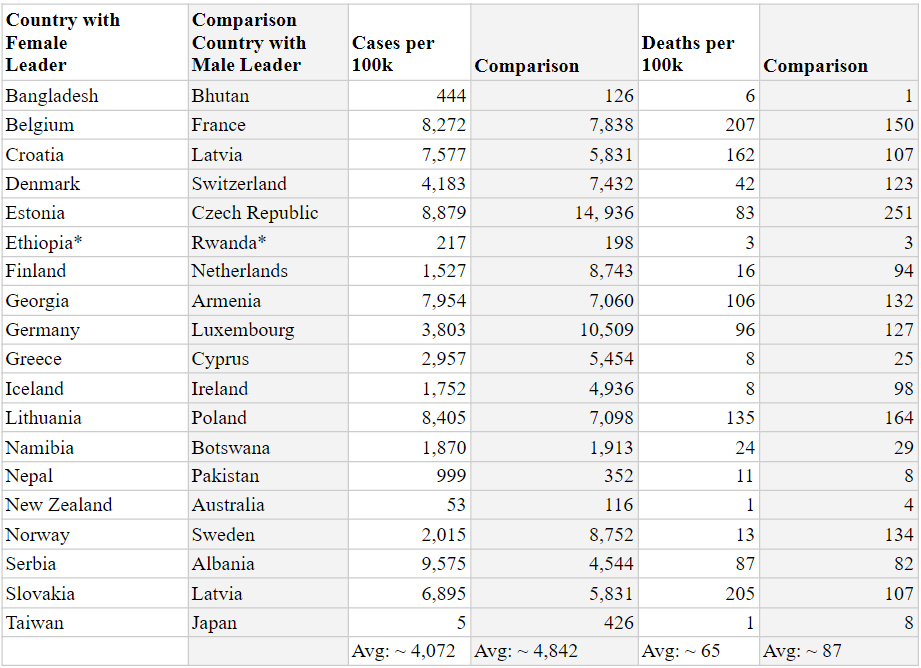

To determine if countries with female political leaders actually did fare better during the pandemic than countries with men in charge, Caroline Mansour studied women’s leadership during the global health emergency as part of Professor Rangita de Silva de Alwis’ class at Penn Law. Caroline picked an analog country for each of the 19 countries with a female political leader by comparing income and wealth per person as well as their democracy ratings and geographic location. She chose not to compare female leaders to the worldwide average because differences in government structure and ability to report data would have obscured any difference from policy decisions.

This analysis shows that women-led countries on average had lower rates of cases and deaths; however, not every female leader’s country performed better than their counterpart. This shows that women’s leadership is not in and of itself the determining factor. To examine which factors allowed countries to succeed, Caroline compared two sets of countries: Taiwan and Japan as well as New Zealand and Australia. All four countries saw relatively less severe pandemic outbreaks, but the women-led countries of Taiwan and New Zealand had under half the rate of cases and deaths compared to their selected counterparts. Ultimately, the countries that protected their citizens the best were led by leaders who made decisive, effective decisions regarding policy; whose messaging and coordination was centralized; and whose messaging was simple, clear, and consistent.

“Women who rise through the ranks to become their nation’s political head must be extremely competent and decisive, and these two qualities overlap with the qualities of successful pandemic management.”

Taiwan and Japan

Despite its proximity to China, Taiwan had one of the most effective responses in the world to the pandemic. They leveraged their experience with the 2003 SARS outbreak to implement an efficient, central command system. As early as December 2019, when Wuhan, China, first began seeing pneumonia with an unknown cause, Taiwan quarantined flights from Wuhan. They leveraged their centralized health system to ensure that everyone had a mask, kept accurate and efficient health records, and used their extensive technological capacities to ensure people observed the necessary 14-day quarantines by creating electronic fences around houses to monitor cell phones. Taiwan also had the legal infrastructure in place to implement restrictions, and they centralized communication between different government agencies to ensure clarity and effectiveness. The early, decisive, and innovative response led to one of the best outcomes in the world.

Japan’s pandemic response was much more effective than the responses of western countries. Nevertheless, it was fraught with fragmented policies and incoherent messaging and mixed results. This is at least in part because the legal framework of Japan limits the power of national actors. Although the federal government was allowed to design basic policies and declare a state of emergency, the legal system put the majority of responsibility on governors or mayors. The federal government was allowed to make recommendations, but governors and mayors had complete autonomy to follow the advice or not. This resulted in mixed messaging from local and national leaders. The national government found Tokyo to be particularly resistant, although it was a hotspot for the virus. Businesses were finally asked to close in Tokyo in November, months after the national emergency began. Furthermore, Japan waited until April 7 to declare a state of emergency, and then it stopped the state of emergency even as cases numbers swelled. Ultimately, the federal government was slow to take action and unable to implement its policies when announced because it lacked the legal power to do so.

New Zealand and Australia

New Zealand’s simple and clear messaging, along with the government’s quick implementation and effective enforcement of the rules, allowed the country to return to normal life while the pandemic still raged in much of the world. New Zealand identified its first case of COVID-19 on February 28, 2020. On March 14, 2020, indoor gatherings were canceled, and the borders were closed. One week later, a 4 tiered system was implemented, and two days after that, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that New Zealand would be going into a Stage 4 lockdown in 48 hours. The state of emergency first ended in May 2020, but every time new cases appeared, a new lockdown ensued. Since March 2021, New Zealand has returned to a normal level of activity, with no restrictions. New Zealand implemented a centralized response and gave clear instructions to its citizens. The color-coded, tiered system allowed citizens to know clearly what was and wasn’t allowed. Furthermore, unlike Australia, the government maintained a strict lockdown for two months before it opened again, and even then, it did not reopen all the way.

Australia has also largely returned to normal life, including plays with packed theaters. However, its response was not as swift as New Zealand’s, and it had more than twice the rate of cases and deaths. In March 2020, Australia experienced a surge of new cases, up to the hundreds per day. The government closed the international borders to foreign nationals and mandated isolation for returning Australians that the police monitored and enforced. When they discovered people were defying the isolation mandate, they moved to isolation in hotels for returning Australians guarded by military or police. Although the level returned to close to zero new cases per day around May, they experienced another surge in July and August. Australia shut down borders between internal states, allowing a state to open based on its own progress, and clearly communicated expectations and boundaries to the public through television. Australia was particularly successful with its Indigenous populations, who demanded to run their own campaigns against the virus and were ultimately six times less likely to catch the virus than the average Australian. Finally, Australia had a strong economic relief program that was able to subsidize hospitality workers and others who were forced to stop working.

Taiwan and New Zealand’s responses to the virus were more effective than Australia and Japan’s for three reasons. First, Taiwan and New Zealand acted early and did not go back to normal until they were sure of the safety. Japan and Australia took more time to implement a response, and the response was less steady when it arrived. Second, Taiwan and New Zealand took centralized actions and clearly and effectively communicated the plan and expectations to their citizens. The muddled messaging in Japan and lack of enforcement at the beginning in both Australia and Japan allowed the virus to progress. Because there was no clarity on the division of governmental responsibility, Japan’s results were uneven. However, in Australia, the Indigenous peoples’ approach to the virus was much more effective than the centralized state. This shows that clarity on the division of power, not the lack of division of power, is the definitive factor. Finally, the governments of New Zealand and Taiwan actively enforced their mandates from the beginning. In Australia, it took some time to implement enforcement strategies like hotels for isolation, and in Japan, the unclear lack of power left the central government unable to enforce their proposals at all.

In a world where so few of the national leaders are women, two of the best pandemic responses were led by women. The gender identity of the political leader of a country is not sufficient to beat a pandemic. And yet, women who rise through the ranks to become their nation’s political head must be extremely competent and decisive, and these two qualities overlap with the qualities of successful pandemic management.

This blog post is part of a larger study conducted by Caroline Mansour as part of Professor Rangita de Silva de Silva de Alwis’ seminar on International Women’s Human Rights Law at Penn Law. Rangita de Silva de Alwis is Hillary Rodham Clinton Gender Equity Fellow at GIWPS and Leader in Residence at Harvard Kennedy School’s Women and Public Policy Program.